The Rev. James Crabb (Part 1)

Sunday, 19th February 2017

Written by Gary

There will be many who read this who have never before heard the name of the Rev. James Crabb, but he was an independent minister and Reverend, who was born in Wiltshire in 1774.

He spent his early years as an itinerant preacher in the Hampshire countryside, later coming to settle and live in Millbrook, Hampshire, where he subsequently died in 1851. During his life, he was a deeply religious man who did much work for the poor and disadvantaged, having first been influential in helping reform the lives of prostitutes 1 and later, perhaps better known for his work in attempting to reform & educate Gypsies; a subject he wrote a book regarding in 1831, called “The Gipsies’ Advocate (Or Observations on the origin, character, manners, and habits, of the English Gipsies)”. 2

His work regarding Gypsies began after he witnessed an event that took place in Lent 1827, when visiting the Winchester Assizes wanting to speak to a chaplain. The event is described in great deal within his book;

The following excerpt is taken from “The Gipsies’ Advocate” by the Rev. James Crabb :-

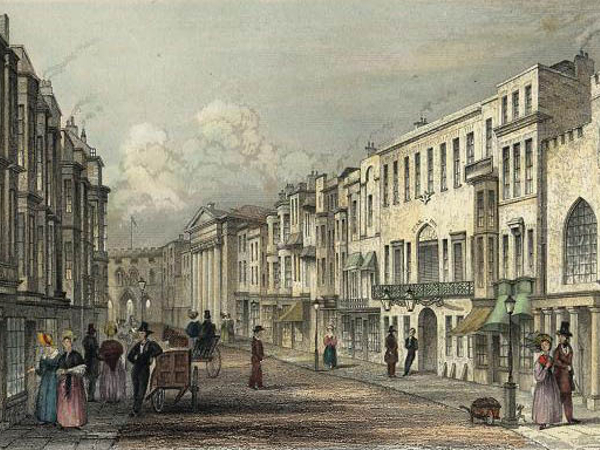

In March, 1827, during the Lent Assizes, the author was in Winchester, and wishing to speak with the sheriff’s chaplain, he went to the court for that purpose. He happened to enter just as the judge was passing sentence of death on two unhappy men. To one he held out the hope of mercy; but to the other, a poor Gipsy, who was convicted of horse-stealing, he said, no hope could be given. The young man, for he was but a youth, immediately fell on his knees, and with uplifted hands and eyes, apparently unconscious of any persons being present but the judge and himself, addressed him as follows;

“Oh! My Lord, save my life!”

The judge replied;

“No, you can have no mercy in this world; I and my brother judges have come to the determination to execute horse-stealers, especially Gipsies, because of the increase of the crime.”

The suppliant, still on his knees, entreated;

“Do my Lord Judge, save my life! do, for God’s sake, for my wife’s sake, for my baby’s sake!”

“No,” replied the judge, “I cannot. You should have thought of your wife and children before.”

He then ordered him to be taken away, and the poor fellow was rudely dragged from his earthly judge. It is hoped, as a penitent sinner, he obtained the more needful mercy of God, through the abounding grace of Christ.

After this scene, the author could not remain in court.

The Rev. Crabb then continues over the course of several pages to detail his interactions with the widow and family of the aforementioned Gypsy, which includes Crabb offering, and eventually taking in, a couple of Gypsy children. The Gypsies widow is apparently also later re-homed and convinced to give up the “sins of her past”, her wandering ways and she subsequently takes solace in the Bible, if we are to take Crabb at his word.

At no point in any of his detailed story telling or explanations, does Crabb list any of the Gypsies names to who he is referring, apart from one William Stanley – a reformed Gypsy – he mentions later in the book. I am unsure if this is an oversight, or perhaps more likely, as Crabb’s book was written only a few years after the aforementioned events take place he may have sought to anonymize those individuals to which he referred. Nevertheless, after picking the book up again before Christmas and coincidentally reading comments regarding Crabb in another book 3, I sought to rediscover just who these Gypsies were as I could find no information on just who they might have been and was surprised that (to the best of my knowledge) no one had tracked them down previous to my attempts at doing so.

I started my research journey with the aforementioned paragraphs taken from Crabbs book mentioning the Winchester Lent Assizes and the trial that he apparently witnessed. The book I happened to be reading at the same time as Crabb’s was David Mayall’s “English Gypsies and State Polices” and a paragraph within it (in relation to the events of the 1827 Lent Assizes and a paragraph I felt the need to prove right or wrong) states,

It is impossible to assess how typical such instances of discrimination were as the relevant records simply do not exist. We even have to accept Crabb’s word that the incident at Winchester took place and was accurately reported by him.

This loosely implied that the Rev. Crabb may have fabricated or exaggerated his witnessing of events, but this has never sat well with me because as Crabb was a man of the cloth, he should at least be expected to be honest with his words. As Mr Mayall’s book is now over twenty years old and records today are far more accessible, he can perhaps be given the benefit of the doubt for not having as easy access to the pertinent records at the time he was writing his book back in 1995 and sure enough, evidence to prove Crabb was indeed telling the truth (although his supplied information is a little confused at times) can be found within assize records and the pages of several different newspapers of the day …

One such example that was recorded on Saturday 17th March 1827 within the pages of The Oxford Journal was that at the Winchester Assizes for March (Lent), the calendar of prisoners contained the names of eighty-four people, yet only two of these were sentenced to death; One David Allee for burglary, and one Francis Proudley – a Gypsy – for Horse Stealing 4 & 5. As Francis was indicted with Reuben Stanley (his father-in-law 6) but Reuben was acquitted, I reasoned I had found the man I was looking for.

In another newspaper article of the day it was expressly written that Francis was the “victim of despair” at his sentencing but prior to his death, he had become “resigned and penitent” 7. This also ties in with Crabb’s written account above of the Gypsy’s (Francis) apparent desperation for the Judge to be lenient with him.

This all but confirmed to me that Francis being sentenced to death was the event the Rev. James Crabb had witnessed and the one profound event that set him on his path to save or reform the Gipsies as he himself states!

Having now discovered Francis identity, what began to unravel – and is still unraveling before me – is the spiderweb of connections that spiraled from this one discovery.

Francis Proudley was most likely the son of Edward & Sarah Proudley and it is probably his baptism that took place on the 12th of September 1802, in Graffham, Sussex, UK (transcribed record, unconfirmed). His wife (and the widow which the Rev. Crabb took in after Francis was hung) was one Patience Stanley, probable daughter of Reuben & Lydia Stanley (Travellers) who was baptised in Beaulieu, Hampshire, UK on the 3rd of March 1805 (again, unconfirmed transcription).

Continuing on after Crabb leaves the court after Francis’ sentencing, in his book he says;

On the outside of the Court, seated on the ground, appeared an old woman, and a very young one, and with them two children, the eldest three years, and the other an infant but fourteen days old. The former sat by it’s mothers side, alike unconscious of her bitter agonies, and of her father’s despair. The old woman held the infant in her tenderly in her arms, and endeavoured to comfort it’s weeping mother, soon to be a widow under circumstances the most melancholy …

Given the time of sentencing in early March, it would appear that the fourteen day old infant was Francis & Patience’s son Vandelow/Vandaloe Proudley who was baptised on the 18th February 1827, in Titchfield, Hampshire, UK (unconfirmed). The three year old child would appear to be the Elizabeth Proudley baptised on the 19th of June 1825, in Milton, Hampshire, UK (unconfirmed) and the fact that moving slightly forward again in Crabb’s book, after he has offered to care for the widows (Patience) children and given her two weeks to consider the offer, she returns to visit him and the book states;

When the fortnight expired, the widow and her aunt again appeared, when the following conversation took place. “I am glad you are come again,” said the friend. “Yes,” replied the widow, “and I will now let you have my Betsy …”

… Betsy of course being a variant of Elizabeth.

After Francis Proudley was hung on the morning of the 24th of March 1827, this left his widow Patience, seemingly alone with two very young children to care for, but this was sadly not to be the end of her troubles …

… Part two will continue next Sunday, 26th February

- The Penitent Magdalen; Or a Narrative of the Life and Happy Death of Jane Thring of Southampton – James Crabb (Religious Tract/Publication, circa 1823)

- The Gipsies’ Advocate (@ The Internet Archive)

- English Gypsies and State Policies – David Mayall (Published 1995)

- Brighton Gazette, Thu 7th September 1826 – Stolen Horses

- Oxford Journal, Sat 17th March 1827 – Winchester Assizes

- Hampshire Chronicle, Mon 18th June 1827 – Horse Recovered

- Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, Thu 29th March 1827 – Winchester, March 24

Article Copyright ©2017

Filed Under: Family Articles

Tags: Crabb, Proudley, Records, Research, Stanley

You Might Also Like To Read …

Archives

Tags

If you like what we do and want to support us, please consider making a secure Paypal donation (however big or small!) to help us continue this project ...